Sunday, March 16, 2008

American Revolution: a preemptive strike against liberty. posted by Richard Seymour

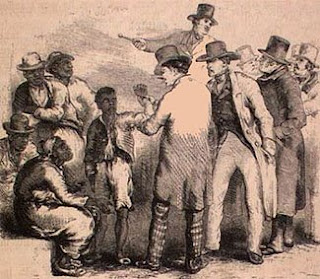

Insult the Founding Fathers as a bunch of genocidal, slave-holding white supremacist patriarchs, and you're liable to irritate somebody's stupid little fetish. You're disdaining 'progress' or 'Enlightenment' or 'modernity' or something of that kind. Or, if your foil is the sort of boorish salon contrarian that likes to babble on about secularism while shovelling enough coke up his nose to cover the Himalayas from peak to base, you might be told that you're being 'obvious' or 'boring'. Of course, producing that sort of reaction is often the best reason for making such statements. But there are other reasons too. The fable of America's origins in liberty and rebellion, and its peculiarly missionary quality, is still one that commands a great deal of irrational support from various quarters, and it is the basis for an unenlightened exceptionalism whose function is to turn the global projection of violence and tyranny into a story of the expansion of human freedom. At most, an acknowledgment of America's serpentine origins in the system of colonial slavery might result in a grudging admission that, after all, progress didn't go far enough on this occasion.

Alfred Blumrosen and the late Ruth Blumrosen, who were civil rights lawyers when not writing history, performed a stunning attack on the commonplace interpretation of the American Revolution as one overwhelmingly motivated by the pursuit of liberty. Their compelling book, Slave Nation, which has been endorsed by no less an authority than David Brion Davis, is by no means politically radical, but the conclusions it draws are radically at variance with the consensus. There is compelling evidence that the revolution, at least from the perspective of the elites who led it and benefited from it, was motivated primarily by the desire to preserve slavery in the face of powerful emancipationist currents in British society, particularly the working class, which were already exerting a profound effect. The background is familiar. The early Hanoverian political order, issuing from the first truly capitalist settlement, was also a comparatively libertarian one for the colonists. Guaranteeing a number of minimum rights to subjects of the constitutional monarch, it both excluded the masses from political power and produced a doctrine of patriotic liberty - the 'freeborn Englishman' - that was fully compatible with the lack of democracy, various kinds of coerced labour, and rigid class rule. It was a doctrine that would be appropriated in various ways: used to justify war against England's colonial opponents by Pitt the Elder (the early days of democratic intervention); taken up as a weapon of opposition by John Wilkes; and of course conscripted to the cause of the American revolt. Given the pace of economic development in the colonies, the control exerted on matters of trade by the ruling oligarchy in London was a burden and increasingly depicted as a violation of the rights of all the freeborn colonists. The development of radicalism in North America was coterminous with an increasingly radical domestic critique of Hanoverian Britain, and it was the ideology of individual liberty that sustained both.

Anti-slavery activism was increasingly evident in both the colonies and in England itself, again rooted in an asserion of the rights of the individual against tyrants of all kinds. In London, freed slaves were encouraging slaves brought back to the metropole with their master to rebel and escape, while radical activists such as Granville Sharp were waging legal battles to win freedom for slaves. In the American colonies, the anti-slavery movement was pioneered by the Quakers. Its demands made an impact on the direction of the Patriot movement and were reflected even in the gestures gestures and words of those who were up to their necks in the slave trade. So far, so familiar. What then follows is that the libertarian impulse, which radicalised in the course of the revolution, helped trigger the revolution in France and provided an opportunity for Haiti to throw off the shackles of slavery and produce the first serious omen that the institution was untenable in the long run. In doing so, it also contained the seed of the future liberation of slaves in the United States. Through a close reading of Locke, as President Bush has suggested, the American revolutionaries made individual dignity and freedom the abiding concern of what has become the world's most powerful state, turning the latter into a matchless arsenal of liberty.

But suppose that a significant motive behind the American revolution, a far more compelling immediate cause of revolt than taxation, was the defense of the institution of slavery - that, so far from being merely accomodated by revolutionaries, or conserved by them in spite of their rhetoric, it was actually a major cause of the revolt? The Blumrosens show that a potentially devastating legal precedent, a victory of anti-slavery advocacy in England, added flames to the tinderbox and ensured the cooperation of colonial elites to preserve the institution of slavery through the declaration of independence. In 1772, a slave named 'Somerset' by his master, an accomplished colonial entrepreneur named Charles Stewart, had been baptised and sought his freedom in England. He was recaptured, enchained, and placed on a ship to Jamaica where he would be sold. Those who had agreed to be his godparents petitioned the King's Court on his behalf and - because of the previously successful legal advocacy of Granville Sharp, were able to win a decision to let him go, since his detention by force was incompatible with the laws of England. It was not that one slave had been freed - it was that any slave in England might, because of this precedent, claim the right to leave his or her master. And the news got around.

The colonial context provided some reason for slaveholders to be alarmed. Colonial legislation could easily be overruled by the Privy Council, and already had been several times. The British imperial power had faced opposition to its taxation policies, and even stimulated serious revolutionary upheaval for short periods. It had perpetrated the infamous Boston massacre against opponents of its rule (one of those 'motley crews' of multiracial workers discussed by Linebaugh and Rediker). But even so, most of the insurgency had died down until the affront of 1772. If parliament asserted its supremacy in relation to the colonies, and the highest legal opinion in England held that slavery was such an odious state of affairs that it could not be permitted in England, might not a skilled campaign with mass support actually obtain the judgment that the colonies as territories subordinate to His Britannic Majesty were subject to the same law? The rise of slavery had enabled the colonial ruling class to contain social discontent in the south by phasing out white indentured labour, permitting white workers to own one or two slaves and thereby enabling them to school their children and reduce the burden of labour they had to contribute toward their own existence. It was seen as an essential component of the southern system, but the same senior spokesman for the British colonial administration who had represented the government in imposing the stamp tax was now also responsible for describing their system as 'odious'. Virginia slaveholders were terrified that their slaves would take the opportunity to rebel, run away, and take their chances with the mother country. The southern colonists started to look at ways to secede, but they could not be sure that the northern colonists would join them in a bid to protect slavery: slavery was less common in the north, though still legal there, and anti-slavery agitation was more common. It has been imagined that the petition by the Virginia colonists requesting that the King abolish the international slave trade was an appeal to end slavery - clearly, no such thing. The fact was that the domestic slave population could reproduce itself, at least in Virginia if not in other parts of the south where conditions were more harsh. And voices were beginning to be raised that the importation of so many blacks was diluting the culture and intellectual advancement that whites could bring to bear. But what it did was permit a vague anti-slavery flavour, which Jefferson could take up without actually calling for the abolition of slavery itself (there is, as Gerald Horne writes, some doubt about the sincerity of his earlier anti-slavery opinions, but no doubt that he later drifted toward the belief in a biological inequality of races).

So, it was the Virginia Resolution calling for intercontinental correspondence on the topic of Britain's abuses that first united the previously disunited colonies, leading to the first Continental Congress in 1774, which sought to assert the rights of the colonies with respect to their property. This was more than demanding the resolution of taxation issues, which could have been achieved without declaring independence from parliament. It was about ownership of all varieties, particularly of slaves. The southern rebels were able to cut a deal with John Adams, representing the other significant colony of Massachusetts, in the defense of slavery, and Adams would continue throughout the revolutionary era and beyond to resist all moves toward emancipation. Subsequent declarations repeatedly asserted and defended the rights of the 'peculiar institution', and it was no incidental matter that the British would try to fight its counterinsurgency war on the cheap by encouraging slave rebellions. If the colonists drew on Locke's 'natural rights' theory to justify their independence, they had to prevaricate where this seemed to conflict with their defense of slavery. Jefferson provided the relevant tweaking: instead of all men being 'born' equal, they were 'created' equal. A state of manhood and thus equal right could thus be 'created' by the decisions of white slaveholders looking at the case of slaves whom they might wish to manumit. The Articles of Confederation would specifically defend slavery's mandate across the states and implicitly rebuke the 'Somerset' decision.

And so on - without the original stimulus and the congress in 1774, without the deal over slavery ensured, northern and southern elites could not have united. There would have been no American nationhood since, until that point, the colonies were more integrated into the imperial centre than one another. Without the sustained efforts to preserve slavery by northern and southern revolutionaries, there would have been no revolution, or at least not then. That the 'pecular institution' would go on to exert such a dominating effect over the political life of the country, both in its domestic and foreign policies, is hardly surprising. It was the 'property right' par excellence, the reason for the revolt, and the basis for the future prosperity of the independent colonies.

Labels: american revolution, capitalism, hanover, progressivism, slavery, stageism