Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Hungarian Revolt and 'totalitarianism'. posted by Richard Seymour

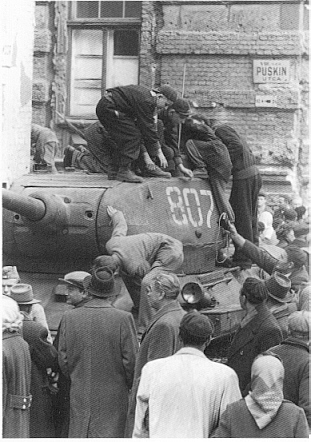

You know, of course, that the Hungarian revolutionaries demanded more and better 'totalitarianism', not less? I speak here as if 'totalitarianism' was a synonym for any non-liberal social system, which is more or less exactly what it is. The Hungarian revolutionaries demanded genuine socialism, socialism from below. It wasn't one of these turgid, rock-festival revolution-lite affairs either: these guys were serious, and armed to the teeth. It is ironic that this anti-Stalinist socialist insurrection has been appropriated as an icon of the struggle for Western freedom during the Cold War. The standard picture of the Hungarian Revolt runs something like this: the Soviets sent their tanks in, overthrew a democratically elected government, nationalised everything, run down the economy like only commies know how, and this led to a civil revolt in favour of Karl Popper's Open Society.

But the revolutionary councils and the workers' councils actually dared to democratise the factories and plants, and real power lay with them, not initially even the Imre Nagy government. They not only sought to get rid of unpopular regulations, but to manage the factories as collective socialist enterprises. The UN report on the crisis conceded that "Steps taken by the Workers’ Councils during this period were aimed at giving the workers real control of nationalized undertakings and at abolishing unpopular institutions, such as the production norms." The report goes on:

"When these Soviet forces succeeded in crushing the armed uprising, it was again the Hungarian workers who continued to combat, by mass strikes and passive resistance, the very régime in support of which Soviet forces had intervened. In every case, the workers of Hungary announced their intention of keeping the mines and factories in their own hands. They made it abundantly clear, in the Workers’ Councils and elsewhere, that no return to pre-1945 conditions would be tolerated. These workers had shown all over Hungary the strength of their will to resist. They had arms in their hands and, until the second Soviet intervention they were virtually in control of the country. It is the Committee’s view that no putsch by reactionary landowners or by dispossessed industrialists could have prevailed against the determination of these fully aroused workers and peasants to defend the reforms which they had gained and to pursue their genuine fulfilment."

This is not merely the "view" of a committee of capitalist plenipotentiaries, of course. It is unambiguously the case. The US naturally hoped that they could utilise the situation in Hungary, send in Special Forces and claim the territory for Western capital, but decided that it was "unpromising". They hoped to utilise Hungarian nationalism which "on its positive side, is Christian and pro-Western", and to mobilise resentment against "the disproportionate number of Jews in high official positions". This revolt did not meet America's criteria: it did not promise to bring a racist, Christian nationalist, pro-capitalist movement to power. And so, the US restricted itself to PR, whispering sweet things to the insurrectionists through Radio Free Europe, with a dim hope of persuading Hungarian workers that the capitalist bloc was their friend.

The revolutionaries almost won, in part because Kruschev didn't want to end up looking like the Anglo-French-Israeli invaders in Suez. This linked article from the BBC, by the way, tells you nothing about the nature of the revolt, merely that it sought extrication from the Warsaw Pact and under an Imre Nagy government. Because of that, it manages to portray the US as a well-meaning giant, unable to "liberate" Hungary at the time, when the plain fact is that they wanted no part of a genuinely socialist Hungary. But a celebration of workers control of industry and the abolition of exploitation would be the wrong message for BBC viewers.