Tuesday, June 20, 2006

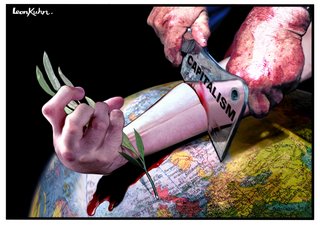

Imperialism, feudal and capitalist. posted by Richard Seymour

And here we are, brothers and sisters, boys and girls, gathered for another spell of extemporaneous exposition on matters marxist. I know many of you, having read this, will go to your beds tonight with tails still aloft and wagging, but those of you whose brains shrivel into walnuts when I begin talking like this will, I trust, go back to the Soduko game. However, I have tested this piece with an audience broken down by age, occupation and sex - namely, me - and found it satisfactory enough.1.

First the obvious: The relationship between capitalism and imperialism is variously and controversially defined. Ha! If ever superfluity and mellifluity were more convivially introduced to one another than in my prose, I have yet to hear of it. Now my stall (which I have stolen from the 'political marxists'): I shall say that capitalism developed in already imperialist societies, particularly England, and transformed the nature of imperialism, in some ways making it more brutal and exploitative. In describing the relationship, understanding the nature of capitalism is crucial (here comes the Brenner thesis that some find so problematic). I would argue against the equation of capital with commerce that a number of authors make – for instance, Fernand Braudel has capital developing first in the use of money and credit in Renaissance Italian city-states. Similarly, Eric Hobsbawm locates a precocious capitalist class alongside the elements of the capitalist mode of production in late medieval societies, particularly in the Mediterranean. These ‘feudal capitalists’ in his account failed to break through because they were ‘parasitic’ on the feudal world, unable to bust out of the feudal integument and create the world in their own image. (Fernand Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century, Volume I, 1981, chapter 7; Eric Hobsbawm, ‘The General Crisis of European Economy in the 17th Century’, Past and Present No 5, May 1954). These accounts are similar to those of ‘dependency theorists’ who argue that capitalism is a system of world-wide exchange characterised by monopoly, in which the same processes which cause ‘development’ in the metropolis causes ‘the development of underdevelopment’ in the periphery. In Andre Gunder Frank’s thesis, capitalism emerges from “a commercial network spread out from Italian cities such as Venice and later Iberian and Northwestern European towns to incorporate the Mediterranean world and sub-Saharan Africa and the adjacent Atlantic Islands in the fifteenth century.” (Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, 1979). Similarly, for Immanuel Wallerstein, the defining aspect of a social system is “the existence within it of a division of labour, such that the various sectors or areas within are dependent upon economic exchange with others for the smooth and continuous provisioning of the needs of the area.” (Immanuel Wallerstein, The Capitalist World-Economy, Cambridge University Press, 1979). In this view, imperialism is structural to capitalist development, which could not have developed without the uneven exchanges imposed on the imperial periphery by the metropolitan centre.

Instead of that caper, and jolly fine caper it is too, I suggest that the ‘political marxists’ are correct to insist that capitalism is not merely the augmentation of commerce that Frank describes, is not the trade-based division of labour that Wallerstein describes – rather, one must distinguish capital-as-wealth from capital-as-social-relation. In the view of Brenner, Meiksins Wood, Holstun, Comminel and Teschke, capitalism developed as an unintended consequence (the 'law of unintended consequences' is not unknown to marxists) of lords and peasants in late medieval England trying to reproduce themselves. Following the catastrophic rural crisis of the 14th Century, peasants in the West of Europe were able to escape the re-enserfment that be-fell peasants East of the Elbe. In France, peasants were to end up owning the bulk of the land on which they reproduced themselves and thus gain considerable independence from the lords, but in England, feudal landlords were able to acquire ownership of most of the land – through enclosures – while transforming copyhold tenure into leasehold, which would allow them to set contract terms on the expiry of a lease. Being thus divorced from their means of reproduction, peasants were obliged to compete effectively, to “specialise, accumulate and innovate”. (Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View, Verso, 2002, chapter three; James Holstun, Ehud’s Dagger: Class Struggle in the English Revolution, Verso, 2002, chapter four). Brenner explains:

Thus we have, classically in England, the rise of that ‘three-tiered’ relation of landlord/capitalist tenant/free wage labourer, around which Marx developed much of his theory of capitalist development in Capital. On the one hand, this capitalist agrarian structure made possible, to an unprecedented extent, the accumulation of capital especially through innovation in agriculture. On the other hand, the same structure made such productive investment ‘necessary’, at least in tendency.

So, in the first place, the landlords had been able to gain control over large consolidated blocks of land. This was a result not only of the decline of serfdom, but of the general short-circuiting of the emergence of small peasant proprietorship in the land—a process to which I shall return below. Large farms appear to have made possible the introduction of new techniques—notably up-and-down husbandry and various systems of irrigation—which transformed agricultural production. Those techniques appear to have been far more adaptable to large-scale production requiring large holdings, than to peasant agriculture. (Robert Brenner, ‘The Origins of Capitalist Development: A Critique of Neo-Smithian Marxism’, New Left Review 104, July-August 1977).

The importance of this assessment is that capital as social relation brings imperatives to improve labour productivity, constantly invest, and thereby revolutionise the means of production – constantly. Primitive accumulation (the ‘so-called primitive accumulation’, Marx called it) is precisely the process of divorcing the bulk of the population from its means of reproduction – not simply accruing wealth through mercantile pursuits or the ‘putting-out’ system. Capitalism cannot, therefore, have been simply lurking in feudalism’s interstices, awaiting the ‘bourgeois-revolution’ (an ideal-type that in no way corresponds the bourgeoisie’s actual role in any of the revolutions called ‘bourgeois’). If Hobsbawm had looked at it from this point of view, he could not have said that “feudal capitalists” in Italian city-states misinvested their capital on buildings, lending and “immobile investment” without really being able to explain why. Hobsbawm suggests that it is because the capitalists were parasitic on the feudal world, but that itself demands explanation more than it explains. (Hobsbawm, op cit; Wood, op cit, chapter two).

2.

There are some interesting critiques to and contrasts of this view that merit consideration, since this impacts crucially on how imperialism develops. Michael Mann, the Weberian social theorist, asserts that the “feudal mode of production” was finally broken by the market, and that a “differentiation among the peasantry” “stimulated early capital accumulation”. The capitalists are “rich ‘kulak’ peasants”, who used poorer peasant labour as “commodities”. In this analysis, it was the peasants lengthening their leases and weakening the feudal lords such that they had to lease out their demesnes and convert labour services into money rent – and the decisive element was the market, which allowed peasants to acquire such a surplus as to be able to pay off dues with cash or kind, rather than labour services. It was the market that enabled peasants to resist re-enserfment, then, and the absence of servile labour across much of Western Europe by 1450 is thanks to the market. (Michael Mann, The Sources of Social Power, Vol I: A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760, Cambridge University Press, 1986, chapter 12). The problems with Mann’s account are numerous. In the first place, the absence of serfdom is not sufficient to bring about capitalism. One can simply be a subsistence producer. Secondly, if markets and an independent peasantry were a sufficient solvent of feudal relations, then capitalism ought to have developed in France first, since French peasants came to directly own 80 to 95% of cultivated land, while the English aristocracy had much greater ownership of land. (Wood, The Pristine Culture of Capitalism, Verso, 1991; Mann, op cit, chapter fourteen). If Mann was right, then France would have been the leading vector of capitalism in the world, rather than England. The ‘rich peasants’ who he says colluded with the absolutist state in keeping social-property relations pre-capitalist, would surely have formed an insurgent capitalist class. Mann’s account is close to that of Maurice Dobb, whom he draws from. For Dobb, the origin of capitalism is in the rise of small producers – richer peasants and yeoman – who began to employ wage labour. This points to another problem – with both Dobb and Mann in this case – which is that they discuss the existence of a propertyless rural proletariat which works for the kulak – but this class had to be created in order for rich peasants to treat them as commodities in the first place, and that had to happen not through market mechanisms, but through enclosure: in short, there had to be a class struggle. The assumption is consistent with the commercialization model: capitalism simply develops within feudalism, and awaits liberation from its fetters. (Wood, op cit, 2002, chapter two; Brian Manning, ‘The English Revolution and the Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism’, International Socialism, 2:63, Summer 1994).

From a more orthodox marxist point of view, Alex Callinicos takes issue with Brenner for having apparently ignored the role of merchants in the development of capitalism, with an excessive focus on agrarian, aristocratic capitalists. Callinicos comments that Brenner does sometimes admit that these “transitional” social forms exist, but they remain unintegrated into his overall account of the development of capitalism. Further, Callinicos adds that Brenner’s account of the role of the smaller merchants in the English Revolution, as capitalists operating in the New World, conflicts with his earlier views and with his antipathy to the idea of the ‘bourgeois revolution’. Perry Anderson makes similar criticisms, suggesting that Brenner has been obliged to acknowledge the role of the ‘revolutionary bourgeois’. Yet, Brenner’s account is finished off with a lengthy postscript that easily answers these criticisms. Callinicos’ first criticism is dealt with by the simple reiteration of Brenner’s long-established thesis that capitalism was initiated by the self-transformation of agrarian aristocracy – that being the case, insofar as a section of the merchant bourgeoisie was capitalist, it is precisely because of the already established transformation in social-property relations. The second criticism, made by both Anderson and Callinicos, dealt with by pointing out that the leading bhurger stratum was not capitalist, but relied on the protection and privileges afforded it by the feudal state – consequently, this stratum failed to rally to parliament’s side. A more substantial criticism, I think, is that Brenner offers an ideal-type or hypostatized view of capitalism, in which characteristics derived from Marx’s abstract model are “privileged” above concrete exploration of how capitalism came about and how it can take various forms. I’ll return to this later, since similar criticisms are made of Benno Teschke. (Alex Callinicos, Theories & Narratives: Reflections on the Philosophy of History, Polity Press, 1995, chapter three; Robert Brenner, Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London’s Overseas Traders, 1550-1653, Verso, 2004, postscript; Perry Anderson, Spectrum: From right to left in the world of ideas, Verso, 2005, chapter twelve).

3.

The consequence of all this for a marxist account of imperialism is not that capitalism is unrelated to imperialism, or did not develop with the assistance of imperialist transactions. It is rather that capitalist imperialism is of a different kind to mercantile or Roman imperialism, as Lenin pointed out. (VI Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, 1939, chapter 6). The origin of colonial expansion in the early-modern period is, as Benno Teschke argues, a function of the lack of an inherent compulsion toward innovative and augmentative production under feudal social-property relations. It was rational to expand territorially in order to grow, and in its mercantile phase, feudalism would achieve massive profits often by simply controlling the trade in goods through maritime power and chartered monopolies. (Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics and the Making of Modern International Relations, Verso, 2003, introduction and chapter 2; Justin Rosenberg, Empire of Civil Society, Verso, 1994, chapter two). The tendency for absolutist, dynastic, or imperial states was to fight wars over succession and for territory. These were not to do with capitalist imperatives or the prerogatives of a national state. (Teschke, op cit, chapter seven). Territory was, once acquired, often circulated, thus disrupting the fixity of identity between state and territory that defines the nation-state. Territory was defined by nebulously controlled frontiers which shifted, rather than fixed borders. Within these frontiers, diverse tax laws and legal codes applied. (Ibid; Anthony Giddens, The Nation-State and Violence: Volume II of A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, Polity Press, 1985, chapter four).

The consequence of all this for a marxist account of imperialism is not that capitalism is unrelated to imperialism, or did not develop with the assistance of imperialist transactions. It is rather that capitalist imperialism is of a different kind to mercantile or Roman imperialism, as Lenin pointed out. (VI Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, 1939, chapter 6). The origin of colonial expansion in the early-modern period is, as Benno Teschke argues, a function of the lack of an inherent compulsion toward innovative and augmentative production under feudal social-property relations. It was rational to expand territorially in order to grow, and in its mercantile phase, feudalism would achieve massive profits often by simply controlling the trade in goods through maritime power and chartered monopolies. (Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics and the Making of Modern International Relations, Verso, 2003, introduction and chapter 2; Justin Rosenberg, Empire of Civil Society, Verso, 1994, chapter two). The tendency for absolutist, dynastic, or imperial states was to fight wars over succession and for territory. These were not to do with capitalist imperatives or the prerogatives of a national state. (Teschke, op cit, chapter seven). Territory was, once acquired, often circulated, thus disrupting the fixity of identity between state and territory that defines the nation-state. Territory was defined by nebulously controlled frontiers which shifted, rather than fixed borders. Within these frontiers, diverse tax laws and legal codes applied. (Ibid; Anthony Giddens, The Nation-State and Violence: Volume II of A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, Polity Press, 1985, chapter four).The commercialization model, adumbrated with reference to Wallerstein and Gunder Frank, would lead one to predict that those colonial powers which were most successful would develop capitalism most quickly. Yet, as Wood points out, Spain was the early dominant colonial power and the leading accumulator of wealth – yet that wealth did not translate into capitalism. Rather, Spain tended to divert that wealth into feudal pursuits – war as extra-economic appropriation, the construction of the Habsburg Empire. On the other hand, the industrial revolution occurred in England – undoubtedly with the growing importance of textiles exports, which relied on cotton imports from imperial plantations – but if industrial capitalism was achieved through exploitation of the periphery by the metropole, then why did even more successful imperialist powers not industrialise before Britain? (Wood, op cit, chapter seven; Wood, Empire of Capital, Verso, 2003, chapter six).

So, what is the relationship between capitalism and imperialism? According to Wood, “capitalism did not put an end to these old imperial practises. On the contrary, it created new reasons, new needs for pursuing some of them with even greater gusto, especially slavery”. (Wood, 2002, op cit, chapter seven). Ireland, for example: whereas pre-capitalist societies preferred land with labour attached – “bondage in the true sense” according to Marx (cited in Teschke, op cit, chapter two) – the dynamic of early capitalist imperialism was to implant the imperatives of capitalism and create economic hegemony. The forcible expropriation of Irish peasants from their lands and its resettlement by Englishmen and Scots consummated under Cromwell a process under way since 1585, and was designed to introduce the methods of English agrarian capitalism into Ireland so as to make it an economic dependency of England. This experience then became consciously adopted as the model for colonialism in the New World. (And in fact it was the new merchants who were to be instrumental in putting up a £300,000 investment in Irish lands to help the state put down the Irish uprising, an investment that paid off with the Cromwellian reconquest in the 1650s), Britain’s first major colonies in Virginia and Maryland were no longer trading posts, but explicitly rooted in the principle of production for profit. (Brian Manning, Aristocrats, Plebeians and Revolution in England 1640-1660, Pluto Press, 1996, chapter four; Wood, 2002, op cit, chapter seven & 2003, op cit, chapter five). Capitalist social relations also laid the groundwork for England’s imperial success, for example, providing it with the wealth necessary to defeat rivals such as Napoleonic France. (Wood, 2003, op cit, chapter six). And it was the defeat of Napoleonic France that established Britain’s Free Trade empire, at least until the 1870s.

However, here lies the rub: for Wood and Teschke, the British empire was obliged to turn to non-capitalist forms of rule to sustain its profits – in India, particularly, but also in Africa. In India, for example, the British were according to Wood drawn into the extraction of revenues by “Company and state” – of course the capitalist nature of British society meant there was a profound pressure to move toward a capitalist imperium, but precisely the very nature of Britain’s capitalist development and its attempt to subsume India into the logic of the market depressed the price of Indian goods and suppressed the development of indigenous industry, thus making it more attractive as a source of “direct coercive exploitation” – in short, “the imperatives of capitalism were constantly off-set by the logic of an imperial military state, which imposed its own imperatives”. Similarly, Teschke argues that the monopoly companies set up by the state for colonial purposes in Africa and India could not be either capitalist or a transitional form, because the “structural nexus between the economic and political” represents the precise “opposite of modern capitalism”. This has been exposed to some trenchant criticisms. China Mieville notes that this assumes the contours of capitalism rather than scrutinising actually-existing capitalism: it sets up an ideal-type, a hypostatization of capitalism in which the intrusion of the political into the economic is necessarily pathological to capitalist social relations. Actually-existing capitalism happens to be replete with instances of state penetration into the economy via public ownership. Indeed, some capitalist states have actually been dependent for their strength and functioning on their ownership of huge segments of the economy – for instance, the Iraqi state’s nationalisation of the Iraq Petroleum Company, which accounted for 90% of the country’s revenues in 1979. By the mid 1970s, the Bangladeshi state was in possession of 85% of ‘modern industrial enterprise’. This is true to a lesser extent of capitalist economies all over the world, including the most liberal, yet Teschke and Wood’s logic would have them consider this non-capitalist. This is especially ironic since Teschke emphasises that he takes a “processual perspective” on international relations. Such an attitude to capitalism would invite the possibility that wage labour and the extrusion of the political from the economic are tendencies rather than always-already fully developed features of capitalism. In this sense, it could be argued that the mercantile phase of empire embodied both capitalist and feudal imperatives: both the reliance on the state and the drive to accumulate. There is also a sense in which the state can itself act as capital: subject to extraneous competition, and driven in that way to improve labour producitivity and thereby surplus extraction - this is particularly the case in those societies which we usually call Stalinist, but it happens to be in evidence in practically all advanced capitalist societies to some extent. Alex Callinicos’ criticisms of Brenner in this respect might also seem apt: if mercantilism can function as a mediator between feudalism and capitalism in India, perhaps the same is true of early-modern England. However, there is an important sense in which the Companies in India began to operate on semi-capitalist principles because capitalism had already been established. Commerce can take both a feudal and a capitalist form, and the direction it will take must depend to some extent on the social formation in which it is embedded. (Wood, 2003, op cit, chapter 5; Teschke, op cit, 2003, introduction and chapter six; Mieville; op cit, chapter five; Malcolm E Yapp, A History of the Near East Since the First World War, Longman, 1996, chapter nine; Colin Barker, ‘The State as Capital’, International Socialism 2:1, Summer 1978).

And there ends my little soujourn. Put comments below.