Saturday, March 11, 2006

France: Capital, Class and Fascism. posted by Richard Seymour

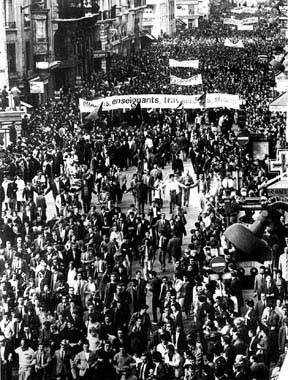

Following recent protests by young French workers and students, further protests erupted yesterday over the attempt by the government to downgrade working conditions for those aged 18 to 25. Students occupied the Sorbonne university, the first time the university has been occupied since 1968. The neoliberal 'reforms' are deeply unpopular, with 55% of French voters demanding their repeal and labour and socialist movements unanimously ranged against them. Villepin, never the most popular of French leaders, has seen his popularity slump 11 percentage points because of it. Nicholas Sarkozy, the hard-right 'populist' who issued racist slurs against Muslim youth last November, has been trying to distance himself from the reforms. It won't wash, however, as he is the most fervent advocate of 'free market' economics in the French government and has loudly supported this policy in the recent past, but he is just opportunistic enough to perform a complete volte-face on the issue, perhaps hoping to win over large segments of the lower middle class and rural vote that Le Pen was able to win over some years back. It is also part of his ongoing power struggle with Villepin, whom he accuses of leaking charges of corruption against him.

Villepin is in a curious double-bind over this. As an advocate for French capital, he is implementing this neoliberal assault just as he comes under attack in the EU for increasing protectionism, which he calls "economic patriotism". This probably represents the main concern of French capital: international competition and what capitalists undoubtedly see as unreasonable protection for labour. Timothy Garton Ash reflected the concerns of Europe's ruling class last year: "while Europe is trying to achieve the 35-hour week, India is inventing the 35-hour day. Whatever our 'knowledge-based' advantage, no economy can compete successfully on such terms. Things must change, if they are to remain the same." The British government has been loudly making this case too. I might add that this illustrates perfectly how the exploitation of 'developing states' works to the detriment of workers in the West. Despite the fact that French workers have been rejecting the neoliberal assault for a couple of years, most notably dealing a brilliant blow to the EU Constitutional Treaty last May, the Socialist Party has not been able to increase its support: they will win if the incumbent Villepin is the UMP candidate, but lose harshly if Sarkozy is the candidate. Noticably, the Trotskyist left, the Ligue Communiste Revolutionaire and Lutte Ouvriere, takes a combined 10% of the vote but because their votes are split they will come behind the poujadist candidate Phillipe de Villiers. Unfortunately, the LO is a deeply sectarian organisation and no coalition will obtain there. However, there certainly is a basis for a new radical left coalition comprising the LCR, PCF and Socialist Party members who dissented over the Constitutional Treaty.

Shortly after the loss of the Treaty vote by the SP leadership, most of which supported it, a number of leading party figures started to denounce those who had campaigned against it and called for a split with the Left in the party. Most notable among these was Michel Rochard, the former Socialist Prime Minister and Bernard Kouchner, the former imperial governor of Kosovo. The leadership was purged of Treaty dissenters, and even attacked the right-wing leadership of Attac. These splits are the result of a left realignment in France, rather than the cause of it. Where Jospin's 'plural left' united the radical movement that emerged in Autumn 1995 with the right-wing of the Socialist Party, that coalition broke down in considerable disappointment after Jospin's government watered down its proposed reforms and privatised more industry than previous Tory governments. Jospin was disastrously beaten by Le Pen in the 2002 Presidential elections, but since the formation of a right-wing government under Chirac there have been repeated fight-backs by French workers and students. As Jim Wolfreys notes, however, the Tory government has succeeded in passing most of its agenda, using the colourless Raffarin to impose its policies before making him a scapegoat when the Constitutional Treaty was lost. So what is happening?

Well (from Wolfreys again):

‘In recent years,’ remarked the sociologist Emmanuel Todd in November 2005, ‘French political life has been nothing but a series of catastrophes. And each time the ruling class’s lack of legitimacy becomes more flagrant’

Social democracy has proven itself useless to the working class in this respect. The ruling class's hegemony is weak, Yet:

[T]he link between social democracy and its popular electorate is deteriorating but has not broken. On the one hand, for the first time in a century working people have been deprived of effective political representation. But on the other, the

organisational and institutional infrastructure of social democracy remains, ‘even if its centre has largely fissured and its contours have altered’, and social democratic parties no longer act as ‘producers of meaning’ in defence of the interests of those on modest incomes. Political traditions take a long time to establish and a long time to break down.

...

So while social democracy is no longer able to mobilise around a programme of social transformation, it is able to maintain a level of electoral support by default.

But the history and structure of the French labour movement and left provides opportunities:

[S]ocial democracy has never been as coherent a political force in France as in Britain, historically divided between the Socialist and Communist parties. The same applies to the crisis of France’s main trade union confederations. The fact that a fragmented trade union movement organises no more than one in ten workers means that its leadership is influential, but not as monolithic or as heavily bureaucratised as elsewhere. Frustration at the unions’ leadership of the strikes against pension reform in 2003, dissipating the movement by separate rather than consecutive days of action on nine different occasions, led workers at a mass meeting in Marseille in June 2003 to jeer and whistle at CGT leader Bernard Thibault, greeting him with cries of ‘General strike!’

...

[T]he electoral performance of the Trotskyist left

shows that it is possible to build an electoral base on a platform which counters the pessimism of social democracy by stressing working class potential for self-activity. The movement and its political expression appeared to be unfolding according to parallel or consecutive rhythms until the May 2005 referendum. The linking up of the LCR and the associative network of the radical left with the PCF and parts of the Socialist left during the referendum campaign made a longer term anti-neoliberal alliance a tangible possibility.

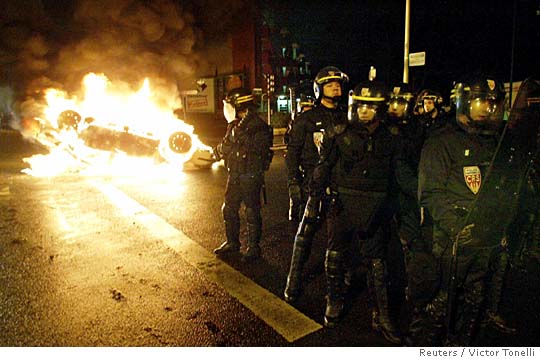

But a tendency to remain aloof from the movement is still a problem for some elements of the far left. LO reacted to the riots of November 2005 by counterposing the youth of the suburbs to the working class, as if the two were somehow separate entities. Worse, the organisation also echoed the racist stereotyping of the riots as the work of ‘yobs’ and petty criminals, attacking those involved for having no social conscience, and deploring, with no trace of irony, their lack of solidarity. LO’s refusal to initiate or engage consistently in political campaigns (anti-racism,anti-fascism, the social forum process, the EU constitution referendum) means that its interventions are generally made in reaction to events, be they those laid down in the electoral calendar, or when strikes and protests flare up.

There is obviously no guarantee that the crisis in French society will continue to redound to the benefit of the Left. For one thing, the present lack of organisation can certainly lead to demoralisation and can encourage a substantial layer of the working class to succumb to the racist serenading of the far right. For another, the lacklustre response of much of the French left to the banlieue riots last year risks leaving those communities a) outside the orbit of the movement, and b) vulnerable to racist attacks. The strategy of Le Pen's National Front has for some decades been to prove that they can successfully manage the state and suppress challenges to capital. It is no surprise that several members of the French ruling class called for Tory a coalition with Le Pen. The intensification of the present crisis could see a substantial layer of the UMP peel off to form such a coalition, perhaps also involving Mr de Villiers, whose main function at the moment is to split the petit-bourgeois right. In short, if the left that emerged from 1995, the anticapitalist movement, the sans papieres, the anti-Treaty campaign and the worker and student resistance to Chirac's neoliberal assault doesn't form a coalition and force a realignment of the Left, as the German left recently did with much success, then fascism is a distinct possibility. It's either socialism, or barbarism.