Monday, December 05, 2005

Shari'a Law and assorted bogey men. posted by Richard Seymour

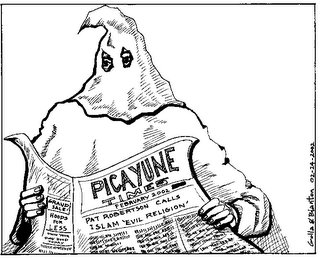

Speaking of populism. It is to be expected that even that coverage of Iraq which is supposedly 'critical' or even 'radical' reproduces some of the underlying ideological bric-a-brac and chimeras that underly imperialist discourse. For instance, this piece, which purports to bring us 'the reality' rather than 'the rhetoric' about Iraq terrifies its readers with descriptions of death squads, oppression and the 'return' of Shari'a law. The mention of Shari'a law catches my attention because, in a way, it would seem a neutral enough term on its own. It is how the term is realised in a discourse that matters - so, when Shari'a law is referred to in an account of the horrors of the new Iraq, it seems primarily to be about creating an atmosphere of barbarism: the new barbarians, laying waste to the Roman imperium, or surging at the gates of Vienna. The term clearly fulfils a very specific ideological function in relation to Western perceptions of Islam. In particular, one thinks of illiberal judicial measures - amputations, corporal punishment, execution, that sort of thing. Kilroy was not merely clacking his pristine teeth together when he referred to Arabs as 'limb-choppers': it is a commonly held prejudice.

I want to do a very quick and inevitably glib and bowdlerised bit of history before coming to my point. First of all, boys and girls, you have to get a rough timetable in your heads. About fifty years after the Rightly Guided caliphs died out, there was the Ummayad empire, then the Abbasids, then after successive dynasties, the Ottomans. The Ummayad family were based in Mecca, but they moved the Caliphate to Damascus after they took Syria from the Romans, and it was a curious signature of these early Muslim rulers that they adapted their rule to that of the previous occupiers of the conquered lands, the models of governance being drawn from pre-Islamic states empire such as Persia and Byzantium. The state wielded most of the power, while the jurists commented on the Shari'a, which was mainly to apply to the affairs of subjects - family relations, market transactions and penal law. In practise, the Shari'a courts were very reluctant to pursue penal matters, which were generally handled by the military or some custodian of the market place, who might mete out a thrashing to some poor thief. They might also issue fines - which was frowned on by clerics, since it implied that one could buy one's way out of having committed a crime.

I want to do a very quick and inevitably glib and bowdlerised bit of history before coming to my point. First of all, boys and girls, you have to get a rough timetable in your heads. About fifty years after the Rightly Guided caliphs died out, there was the Ummayad empire, then the Abbasids, then after successive dynasties, the Ottomans. The Ummayad family were based in Mecca, but they moved the Caliphate to Damascus after they took Syria from the Romans, and it was a curious signature of these early Muslim rulers that they adapted their rule to that of the previous occupiers of the conquered lands, the models of governance being drawn from pre-Islamic states empire such as Persia and Byzantium. The state wielded most of the power, while the jurists commented on the Shari'a, which was mainly to apply to the affairs of subjects - family relations, market transactions and penal law. In practise, the Shari'a courts were very reluctant to pursue penal matters, which were generally handled by the military or some custodian of the market place, who might mete out a thrashing to some poor thief. They might also issue fines - which was frowned on by clerics, since it implied that one could buy one's way out of having committed a crime.The state was content with this because it was and is, in fact, very difficult to convict someone on the basis of Shari'a law. Theft, for instance, had to be witnessed by four male Muslims - which was so infrequent and unlikely that summary justice was usually deployed by secular authorities. Further, if it did come to the religious jurists, they would insist on applying all kinds of minute distinctions - did he break in to a house to steal, did he use violence, did he run away, did he steal the big stuff or just enough to eat etc. The fanatics, dare I say it, were quite pacific next to those who guarded money and property. And, of course, most pre-modern punishments were corporal rather than restrictive. Imprisonment is the modern legal-rational mode of punishment par excellence. But the point to recognise here is that, although Shari'a is associated with the modernist Khomeini doctrine of vilayet e-faqih, there was no more interpenetration between state and society under Islam than there was under Christianity in Europe. At least since the Ummayads, there was a de facto separation of state and society. Formally, the state was run by 'caliphs' and claimed some connection to the Rightly Guided Caliphs: in practise, religion was a legitimising appendage. The soldiers who might once have been considered armies of faith were disbanded and replaced by professional armies, usually Turkish. Some of the taxes applied were stipulated in the Shari'a, but most of those applied were the additions of successive dynastic rulers: sometimes, these rulers would tax the sale of alcoholic drinks, thereby admitting in practise what religion disallowed in theory. Far from being a method of dicatorship, Shari'a was a very loose body of ethical and religious dictums, poorly enforced, and entirely complementary and subordinate to sovereign decrees.

What changed all that was the catastrophic wave of defeats for the Ottomans at the hands of Russia, France & Britain in the mid-19th Century (in the end, Britain propped up the Ottomans as a counter to France and Russia). These prompted the rulers to introduce a wave of reforms aping European modernisation - beginning with military procedures, but also expanding to include administration, education and then law. The latter involved the adoption of European codes - commercial law, penal code and so forth. Similarly, in Egypt, which had freed itself from the orbit of the Ottomans under Ali, Shari'a law had been applied in theory but not in practise - the only exception being Family Law, or Personal Status Law. At some point in the 1860s, some of the reforming ministers introduced the codification of civil transactions in the Shari'a, refashioning it in the image of the Napoleonic Code. (In fact, some reformers were to argue that there was no point in having a Shari'a since if it was codified it was little different to European law, deriving as it did from the same principles.) The religious scholars and students, it has to be said, were not too happy about this: the transformation of religious jurisprudence into state law left many of them without work. Ahmad Jawdat Pasha introduced the confluent changes to Ottoman law by codifying the Shari'a into a Majalla.

What changed all that was the catastrophic wave of defeats for the Ottomans at the hands of Russia, France & Britain in the mid-19th Century (in the end, Britain propped up the Ottomans as a counter to France and Russia). These prompted the rulers to introduce a wave of reforms aping European modernisation - beginning with military procedures, but also expanding to include administration, education and then law. The latter involved the adoption of European codes - commercial law, penal code and so forth. Similarly, in Egypt, which had freed itself from the orbit of the Ottomans under Ali, Shari'a law had been applied in theory but not in practise - the only exception being Family Law, or Personal Status Law. At some point in the 1860s, some of the reforming ministers introduced the codification of civil transactions in the Shari'a, refashioning it in the image of the Napoleonic Code. (In fact, some reformers were to argue that there was no point in having a Shari'a since if it was codified it was little different to European law, deriving as it did from the same principles.) The religious scholars and students, it has to be said, were not too happy about this: the transformation of religious jurisprudence into state law left many of them without work. Ahmad Jawdat Pasha introduced the confluent changes to Ottoman law by codifying the Shari'a into a Majalla. What is curious about this modernisation process is that, typically, it opened up both reactionary and progressive possibilities: both the 'fundamentalists' and the 'progressives' agreed that the Shari'a was not necessarily Divine, but was contingent, written by human beings in accordance with their particular circumstances: to arrive at a truly Islamic society, one needed to apply itjihad (interpretive reasoning) to the texts and derive relevant conclusions. And so, because the texts are so indeterminate, and the procedures for interpretation so tortuous, a variety of possibilities emerged. For instance, the Hashemite regimes in Jordan and Iraq adopted more or less unadulterated the codified Majalla as domesticated, pro-Western regimes, while the Saudi regime maintained a strict Wahabbism with an obviously chauvanistic version of Personal Status Law which allowed men easy divorce and polygamy, while not allowing women divorce except under restricted circumstances. The more radical Arab nationalist regimes, by contrast, attenuated and liberalised Personal Status Law: in Iraq, the Qasim-led Free Officers first gave women the right to divorce and severely restricted polygamous practises, while the first Baathist regime introduced certain laws pertaining to inheritance that were favourable to women. In Egypt, new laws were introduced to give women more power in marriage and curtail polygamy, although there were various sops to the conservatives, particularly after Sadat's assassination. What is notable is that the liberalisation decrees were in most instances justified and legitimised by reference to the Fiqh - the point again being that the texts are sufficiently indeterminate as to allow a variety of interpretations. Shari'a law, strictly speaking, is about as Islamic as European law is Mosaic: it's rather like the Islamic banking institutions which replace usurious interest with 'gifts' and 'rewards' to make it halal. Similarly, the more brutal modalities of Arab nationalist rule - torture, executions, amputations and so on - resulted from secular priorities. Indeed, a quick look at the Saudi regime is enough to confirm how Shari'a is manipulated for secular purposes: I mentioned the difficulty with convicting anyone under Shari'a law earlier; well, the Saudi regime gets around this by extracting 'confessions'. Watertight.

What is curious about this modernisation process is that, typically, it opened up both reactionary and progressive possibilities: both the 'fundamentalists' and the 'progressives' agreed that the Shari'a was not necessarily Divine, but was contingent, written by human beings in accordance with their particular circumstances: to arrive at a truly Islamic society, one needed to apply itjihad (interpretive reasoning) to the texts and derive relevant conclusions. And so, because the texts are so indeterminate, and the procedures for interpretation so tortuous, a variety of possibilities emerged. For instance, the Hashemite regimes in Jordan and Iraq adopted more or less unadulterated the codified Majalla as domesticated, pro-Western regimes, while the Saudi regime maintained a strict Wahabbism with an obviously chauvanistic version of Personal Status Law which allowed men easy divorce and polygamy, while not allowing women divorce except under restricted circumstances. The more radical Arab nationalist regimes, by contrast, attenuated and liberalised Personal Status Law: in Iraq, the Qasim-led Free Officers first gave women the right to divorce and severely restricted polygamous practises, while the first Baathist regime introduced certain laws pertaining to inheritance that were favourable to women. In Egypt, new laws were introduced to give women more power in marriage and curtail polygamy, although there were various sops to the conservatives, particularly after Sadat's assassination. What is notable is that the liberalisation decrees were in most instances justified and legitimised by reference to the Fiqh - the point again being that the texts are sufficiently indeterminate as to allow a variety of interpretations. Shari'a law, strictly speaking, is about as Islamic as European law is Mosaic: it's rather like the Islamic banking institutions which replace usurious interest with 'gifts' and 'rewards' to make it halal. Similarly, the more brutal modalities of Arab nationalist rule - torture, executions, amputations and so on - resulted from secular priorities. Indeed, a quick look at the Saudi regime is enough to confirm how Shari'a is manipulated for secular purposes: I mentioned the difficulty with convicting anyone under Shari'a law earlier; well, the Saudi regime gets around this by extracting 'confessions'. Watertight.Put it another way: even in the vilayet e-faqih set-up in Iran, what the 'guardianship' of the jurists basically amounts to is a buffer to protect capital from the incursions of popular democracy. The reason why it is so repressive and undemocratic is not because of Islam, but because the conservative religious bourgeoisie successfully hegemonised the revolution and were able to determine the subsequent course of events. The Council of Guardians is supposed to simply make sure that legislation is compatible with Islam, and in their hands this tends to mean that conservative 'family values' are upheld while attempts to socialise private property have been suppressed.

The reasons I go through all this are various. Firstly, Shari'a law is something Iraq is likely to have in some variant, whether occupied or not. Precisely how it will be articulated, quite how restrictive or liberal it is, depends a great deal on how the populist anti-occupation movement is hegemonised. The populist call "No No USA, Yes Yes Islam" can be interpreted in various ways - most of them would probably include ending the occupation, nationalising the oil, public works to end unemployment, generous support for the poor. Many of those taking up that cry are likely to be trade unionists of various kinds. This is so far from a settled situation. Second, a phoney excuse for refusing to support the resistance is that they are 'Islamist'. It is unlikely that the grassroots resistance is 'Islamist' in any unified and programmatic sense, although there are certainly Islamist groups operating in it. However, the main question is: so what? Since when did the right of a people to resist occupation have anything whatsoever to do with your preferred ideological comportment? Third, the automatic shiver produced at the mere mention of Shari'a law is symptomatic of the way in which Islam is produced for Western audiences as a freakish sideshow, a chilling horror tale of Cold War simplicity, a noxious brew of fantastic violence and sexual degradation that, inevitably, is a projection of what our rulers are presently inflicting on Iraq.

The reasons I go through all this are various. Firstly, Shari'a law is something Iraq is likely to have in some variant, whether occupied or not. Precisely how it will be articulated, quite how restrictive or liberal it is, depends a great deal on how the populist anti-occupation movement is hegemonised. The populist call "No No USA, Yes Yes Islam" can be interpreted in various ways - most of them would probably include ending the occupation, nationalising the oil, public works to end unemployment, generous support for the poor. Many of those taking up that cry are likely to be trade unionists of various kinds. This is so far from a settled situation. Second, a phoney excuse for refusing to support the resistance is that they are 'Islamist'. It is unlikely that the grassroots resistance is 'Islamist' in any unified and programmatic sense, although there are certainly Islamist groups operating in it. However, the main question is: so what? Since when did the right of a people to resist occupation have anything whatsoever to do with your preferred ideological comportment? Third, the automatic shiver produced at the mere mention of Shari'a law is symptomatic of the way in which Islam is produced for Western audiences as a freakish sideshow, a chilling horror tale of Cold War simplicity, a noxious brew of fantastic violence and sexual degradation that, inevitably, is a projection of what our rulers are presently inflicting on Iraq.