Tuesday, March 30, 2004

Frances Yates and The Scientific Revolution. posted by Richard Seymour

I meant to post this ages ago, but a brief debate with someone yesterday prompted me to recall it...Defining the argument:

In her classic work “Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition” , and subsequent writings, Frances Yates has elaborated a theory of modern science, placing its origins in the Neoplatonism and “Hermetic-Cabalist” traditions which experienced a revival in the fifteenth century, largely due to the translating work of Marsilio Ficino on behalf of Cosimo Medici. In this treatment, I want to argue that Yates successfully establishes a series of connections and family resemblances between magic and modern science, but that her claims for magic exceed what her evidence justifies, while the evidence that she adduces is sometimes tenuous. I think she has also misplaced the causal connection, so I will end by adumbrating a different way of considering the evidence that may avoid the problems of Yates’ interpretation.

Frances Yates

From the Magus to the Mechanic.

"[T]he Renaissance magus", Yates believes, "exemplifies that changed attitude of man to the cosmos which was the necessary preliminary to the rise of science". Indeed, there is no shortage of similarity between the practitioner of natural magic and that of natural philosophy. Sometimes, the distinction is not at all clear. The modern "emphasis upon empiricism and upon 'peering into' nature ... appears in works on natural magic". Giambattista Della Porta, the prolific author on natural magic insisted just as much as Francis Bacon that the way to discover 'such things as lay hid in the bosom of wondrous nature,' was to investigate the natural world. As John Henry points out, "Renaissance natural magicians [insisted] that their form of magic depended upon nothing more than knowledge of nature" - although he also notes that in practise, they relied “heavily upon traditional claims in the magical literature".

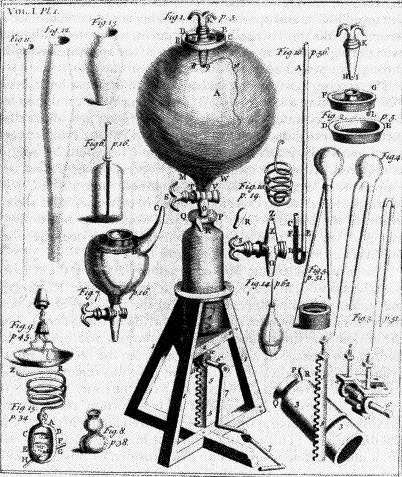

Yates demonstrates both the manipulative and mathematical aspects of magic. The account of man's creation given by the 'Pimander' (one of the Hermetic texts) is one in which the Father allows man to 'produce a work'. "Dominion over nature" is in man's "divine origin", and the magus exercises this dominion "through the manipulation of occult sympathies" running through nature. It is also characterised by what "Agrippa calls mathematical magic", which includes geometry, astronomy, mechanics, arithmetic etc.

Giambattista Della Porta

Pythagorean mathematics (and also the Pythagorean “symbolism and mysticism”) manifested itself in the work of Pico. Neither “Pythagorean number … nor Cabalistic conjuring with numbers in relation to the mystical powers of the Hebrew alphabet, will of themselves lead to the mathematics which will really work in applied science”. But Aggripan mathematics did have a place for mechanical application, or “real artificial magic” as Tommaso Campanella was to call it a century later. Copernicanism may also owe something to the prisci theologi unearthed by Ficino, which, Yates suggests, shook the complacent faith in the Ptolemaic position of the sun.

Yates unearths these connections through a series of archetypes. The Renaissance magus introduces Platonism, the licit manipulation of nature and number into the Christianised natural philosophy of the High Middle Ages. These influences manifest themselves in Leonardo Da Vinci, who cited "Hermes the philosopher" and defined force "as a spiritual essence". John Dee, the 16th Century scientist and mathematician, was known to have attempted communion with spirits, and drew inspiration from Pico. Dee, especially in Yates’ later writings, is the archetypal Renaissance magus.

The next layer is the "Rosicrucian type" who is defined by the need for secrecy in the hostile climate of the counter-Reformation, "an intensely religious temper" while nevertheless remaining unaffiliated to any particular doctrine, and the "Hermetic belief that the deepest truths cannot be revealed to the multitude". The Rosicrucians were influenced by the work of John Dee and Paracelsus. They practised natural magic, especially alchemy. “Rosicrucian alchemy expresses both the scientific outlook, penetrating into new worlds of discovery, and also an attitude of religious expectation”.

John Dee.

Francis Bacon and Father Marin Mersennne exemplify the final stage of the progression from Renaissance magus to modern scientist. Bacon's New Atlantis is a utopia "ruled by mysterious sages who keep the citizens in tune with the cosmos", but who "do not practise astral magic, and are not exactly magi". Bacon's emphasis on technology reflects the influence of Renaissance Hermeticism, just as much as his desire to exercise power over nature. Father Mersenne, on the other hand, rejects the animus mundi, embraces the “modern” corpuscular outlook and those elements of magic compatible with it, and thus completes the transition.

Francis Bacon

A few problems.

It is possible to accept all of Yates’ empirical examples without accepting the thetic relation they support. John Dee, for instance, may well have been “imbued with the importance of mathematics”, but it is questionable whether he discovered anything important. And the magical importance of his ‘numbers’ is not of the classical Cabalistic kind, that of attempting to interpret the scriptures, but rather the ‘book of nature’ which his ‘conversations with angels’ helped him to interpret. This innovation does not explain so much as it demands explanation.

Francis Bacon’s anti-Copernicanism may not be as easy to correlate to his opposition to magic as Yates believes. As Robert Westman points out, of all the ‘Hermetists’, only Giordano Bruno added anything original to Copernican thought, while Hermetic sun-worship is just as compatible with a geo-centric universe in which the sun is at the centre of seven planets surrounding the Earth. “Dominion over nature”, given sanction by the Hermetic tradition, could also be argued to be a feature of Christian faith.

Yates clearly believes that mathematics and magic are essential correlates in this period. But the recovery of the Archimedean texts by William of Moerbeke only led to their general appropriation in the sixteenth century when “the self-educated engineer and mathematician Nicolo Tartaglia” published them in print. The “sixteenth century revival of the classical tradition of mechanics was not in the first place the concern and work of natural philosophy at the universities, but of laymen in classics, namely engineers who were interested in theoretical questions”. It isn't straightforward to assess claims about the transmission of empiricism from magic to science - if dominion over nature was sought, how else to achieve it than to investigate nature? What better way to register its quantities than to make use of the sophisticated systems of mathematics available?

Yates invites doubt when she offers speculation , although she emphasises that as a pioneer in her field she is perhaps obliged to ask more questions than she is immediately able to answer. There are, nevertheless, some dubious interpretive gestures, such as the reference to Father Marin Mersenne as the putative final stage in the progression from magus to scientist. Mersenne was a philosopher and mathematician whose abiding concern was to combat the rising influence of animistic and magical philosophers. Repulsion against magical beliefs propelled his scientific endeavours in this case, and Yates offers no good reason to infer that this is merely the culmination of a transition.

The main aporia, however, is the heuristic. The "chief stimulus of that new turning toward the world and operating on the world" was, according to Yates, what she referred to as the Hermetic tradition. It is difficult to evaluate such claims, or to know when they are proven. Because the rise of magic was almost coterminous with, and certainly related to the rise of science, there was not necessarily a causal connection between the two.

Here's the rub. Many of the strands of magical thought and practise which Yates describes collectively as 'the Hermetic Tradition' were widely known in classical Greek civilisation, even if most of the Corpus Hermeticum should properly be dated to the second and third centuries AD, and the nascence of Christian Rome. Many of these Greek traditions owe themselves to the practises of Egyptian civilisation. Yet, while the Egyptians had much in the way of technology, they had nothing that we would call science. And while the Greeks did develop the beginnings of science, they made few technological advances. In the 800 years from the rise of Athenian civilisation to the fall of the Roman Empire, a wealth of scientific thought proliferated, but there was not the practical empirical approach that we associate with the rise of modern science. (I emphasise practical because the Greeks, notably Aristotle, were acute observers). It was as alien to the Greeks as it was commonplace to the mechanists that one should seek to interfere with nature. Evidently, there is no necessary connection between the existence of magical beliefs and the rise of exact science.

Hermes Trismegistus

While the rise of magic in the High Middle Ages and the rise of science in early modernity are clearly related, they are perhaps best understood as responses to the same opportunities and problems offered by the profound changes taking place in Europe from the year 1000. It would be possible in this view to endorse the bulk of Yates’ findings, while weighing their import differently. One could even argue that magic did provide a necessary precursor to science, but that certain catalysts were necessary to effect the change. The historical context, carefully examined, may yield a few of these catalysts, and the regulating factors which conditioned both the rise of science and the rise of magic. I’m afraid I can only offer a brief outline.

New conditions and dynamic feudalism.

Literacy: While in the early medieval period literacy was restricted to a "thin layer of literate monks and clergy", the layer of traders and artisans which emerged and began to populate towns in the eleventh and twelfth centuries needed both formal law and a written record of accounts and contracts. Literacy was no longer confined to monasteries, nor was Latin the only written language. Whereas the liberty of an urban Greek citizenry was coextensive with rural slavery and thus the almost complete separation of the intellectual elite from production, the educated men of the High Middle Ages were often rooted directly in economic activity. The sphere of thought was joined to that of action, and the philosophy of Francis Bacon exemplifies the resultant outlook.

"Dominion over nature": Such dominion, already established with the water mill and other mechanisations, became part of the perspective of the new intellectuals. Roger Bacon and Nicole Oresme "strove to increase" the domain of mathematics "in the natural world". Roger Bacon was the first European to write down the formula for gunpowder, which was the necessary preliminary for the first use of the cannon in 1320. This presaged the mathematisation of nature of Renaissance humanists, engineers and magicians.

Crisis: But economic crises, famine and plague met the profound advance of these years. Lordly consumption was expensive, as was the increasing tendency to wage war. Acording to George Duby, the "grain-centred system of husbandry began to be unsettled by the requirement of the gradual rise of aristocratic and urban living standards". The result was a series of wars between rival lords and monarchs, and peasant uprisings. As the Black Death swept in from Asia in 1348, perhaps a quarter of the population of Europe, already weakened by famine, was destroyed. Europe was plunged into "ceaseless epidemics, endemic war, and its train of destruction, spiritual disarray, social and political disturbances". It should therefore be no surprise that the "utopias of the Renaissance" cited by Yates are "governed by priests ¼ who know how to keep the population in health and happiness". Or that their inhabitants should be "practisers of astral magic ... deeply interested in ¼ scientific research".

Advancement of Northern Italy: Northern Italy was the most economically advanced region in Europe as the crisis receded, and also the least damaged. Food production had not declined as quickly as the population, and Europe recovered rapidly from its crisis. Rural labourers benefited appreciably from a general rise in income and the consequent dissolution of serfdom. Large merchant families came to dominate the region, such as the Medicis in Florence. Seeing their mercantile wealth as transient, they often sought the more secure status of land ownership, court and church positions. The Renaissance resumed unfinished business, and its primary sponsors were the new merchant families and the courts they frequented. Magic was "courtly science par excellence", largely because it involved precisely the sort of "dominion over nature" that princes and merchants sought to buttress their power.

Conclusion.

Magical practises and beliefs were important for the development of science, but paradoxically only insofar as they encouraged practises and beliefs that were commensurable with a disenchanted outlook. While the relationship of magic to science was not one of pure antagonism, neither were they coextensive. Both magic and science, while neither passive reflections of social causes, nor rigidly determined by the economic base, can be seen as related to attempts to solve pressing problems and grasp real opportunities afforded by the zenith and crisis of European feudalism.

ENDNOTES:

Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge, London and New York, 1964.

Frances Yates, “The Hermetic Tradition in Renaissance Science”, in Art, Science and History in the Renaissance, Charles Singleton (ed.), 1967 (p. 226).

William Eamon, “Court, Academy and Printing House: Patronage and Scientific Careers in Late Renaissance Italy”, in B T Moran (ed.), Patronage and Institutions, 1991, (p21).

Ibid, (p 28).

John Henry, The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science, 1997 (ch. 3, p. 44).

Yates, 1967, op cit (p. 228).

Yates, 1965, op cit (pp. 164-5).

Ibid, (p. 170).

See, for example, Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, 1979, Routledge, London and New York, (pp 92-127).

Ibid, (p 199).

Yates, cited in H. Floris Cohen, The Scientific Revolution: An Historiographical Enquiry, 1994, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, (p 172).

Yates, 1964, op cit, (p431). This explanatory gesture rings of the Hegelian “negation of the negation”; Aristotelianism is negated by Neoplatonism and magic, the latter negated by mechanism and the Newtonian synthesis.

A. Rupert Hall, cited in Cohen, op cit , (p. 290).

Deborah Harkness, John Dee’s Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy and the End of Nature, University of California, 1999, Cambridge University Press (pp. 181-2).

Cited in Cohen, op cit, (p 292).

For example, Genesis I:25 “Be fruitful and multiply…” cited by Francis Bacon.

Wolfgang Lefevre, “Galileo Engineer: Art and Modern Science”, in Jurgen Renn (ed) Galileo in Context, Cambridge University Press, 2001. (p. 17).

Indeed, the Portuguese used mathematics and astronomy for the purpose of dominating, not nature, but other human beings as they set out to enslave parts of Africa. See Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800, Verso, London, 1997, (p 97).

Some examples from Yates, 1967, op cit: "Was mathematics, for Bacon, too much associated with magic...?" Copernican heliocentricity "might have seemed to Bacon heavily engaged in ... magical and animistic philosophy". "[S]ome of Bacon's mistakes may have been influenced by his desire to rationalise...". Perhaps it was because Dee was an astrologer that “Dee, unlike Bacon, was imbued with the importance of mathematics". The "cult of ... Hermes Trismegistus, may have helped to direct enthusiastic attention" toward Archimedean texts.

Steven Shapin, The Scientific Revolution, University of California, 1996.

William von Staden, “Affinities and Elisions: Helen and Hellenocentrism”, in Michael Shank (ed) The Scientific Enterprise in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, University of Chicago, 2000, (pp 54-71).

Andrew Gregory, Eureka! How the Greeks Invented Modern Science, Icon Books, 2001, (pp 6-22); see also T. E. Rihill, “Greek Science” in New Surveys in the Classics, No. 29, Oxford University Press, 1999, (pp 1-23).

Perry Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, Verso, 1974, (p 28n).

The argument following from this owes itself to Benjamin Farrington, cited in Cohen, op cit, (p248). Farrington argues that by the 1st Century AD and the flourishing of Galen and Ptolemy, the Greco-Roman world had been “loitering on the threshold of the modern world for four hundred years” but could not cross it. Science, he argues, did not fulfil the same social function for the Greeks that it had for the early-moderns, and this is an important part of explaining why there was a Scientific Revolution in the Middle Ages, but not in antiquity.

Guy Bois, The Transformation of the Year 1000: The village of Lournand from antiquity to feudalism, Manchester University Press,1980.

Chris Harman, A People’s History of the World, Bookmarks, 1999.

Anderson, op cit (pp 29-44).

For example, Bacon’s advice to the “studious to sell their books and build furnaces”, so that “human knowledge and human power meet as one”. Cited in Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, 1980, (p. 171).

Harman, op cit.

A. George Molland, “Aristotelian Science” in R C Olby, G N Cantor, J R R Christie and M J S Hodge (eds), Companion to the History of Modern Science, 1990 (p 563).

Harman, op cit.

William Chester Jordan, European Society in the High Middle Ages, 2001, (pp 303-308).

Harman, op cit.

Anderson, op cit, (p 201).

For a striking graphic illustration of this, see Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World: Civilisation and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, Fontana/Collins Press, London, 1979, (p121); also see Guy Bois cited in Harman, op cit.

Yates, 1967, op cit., (pp. 236-7).

Anderson, op cit, (p204).

Eamon, op cit.